They don’t call them “medicinal mushrooms” for nothing…

In a very recent study using human participants, all 3 of these – reishi (Ganoderma lucidum), turkey tail (Trametes versicolor), and chicken mushroom (Laetiporus sulphureus) – aided in clearance of oral human papillomavirus (HPV).

After 2 months of treatment, the combination of reishi and turkey tail was much more effective (displaying 88% clearance of the virus), compared to chicken mushroom alone (5% clearance). While there are numerous strains of this sexually transmitted virus, these mushrooms (i.e. allies, companions, friends) were tested against the strains that cause cancers in 70% of all cases. And they were effective … not in petri dishes, but in humans (International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms, 2014).

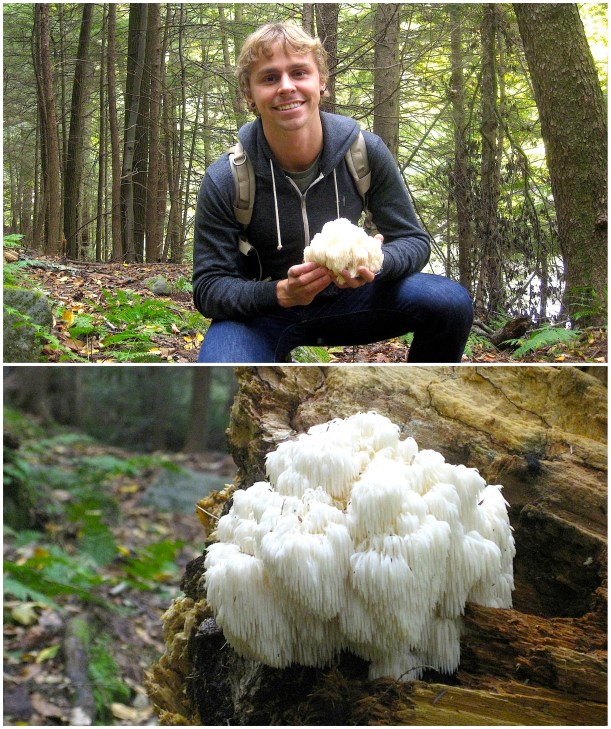

Turkey tail is one of the most ubiquitous fungi inhabiting our woodlands in Pennsylvania. It overwinters, meaning you can harvest it today. The chicken mushroom, while not nearly as effective as the others against HPV, is fairly common and can be harvested early summer through autumn. Experts contend over whether the true reishi mushroom (G. lucidum) grows in North America, and it seems that perhaps this fungus is part of a species complex. Several closely related fungi (i.e. G. tsugae) are common in the American forests, especially in western Pennsylvania.

Meaning … the medicine is all around us, not just for HPV, but for well-balanced optimal health. The question is, how bad do you want it?

For more information on the anti-cancer properties of medicinal mushrooms, please check out an article I wrote for my wild food nutrition blog (Wild Foodism), entitled 3 New Studies Demonstrate The Anti-Tumor Efffects Of 3 Medicinal Mushrooms.