“Hello, what are you doing under there?” I ask.

No response.

It’s a seemingly shy mushroom – never razzle dazzle in appearance. Sure, it has some color – a splash of orange, a hint of green, though it typically puts on a show no larger than that (unlike its fellow forested fungal friends, the Amanitas and Hygrocybes, though they’ve been reduced to mycelia by now).

You might want to take some Panellus serotinus home. “It would be my pleasure,” the mushroom says. Panellus serotinus is edible of course, though in order to really make a dish out of it, prolonged cooking methods are suggested.

And hey, not that you asked for it, but Panellus serotinus will be sure to throw in a dash of immuno-modulating and anti-tumor oomph, because … well … that’s what it has been shown to do (Kim et al., 2012).

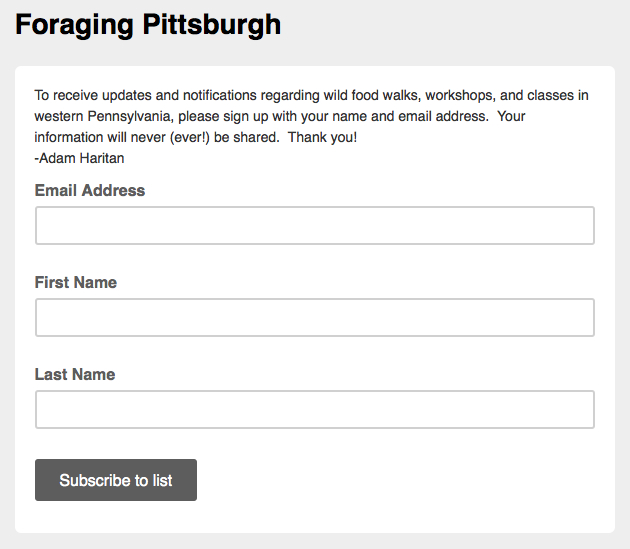

Look for the late fall oyster mushroom today in western Pennsylvania (this photograph was taken in Moraine State Park). Even in the snow covered forest, even in these frigid temperatures … the best that the universe has to offer is out there – always wild, always free.